|

A

Practical View of Regeneration Part II A

Practical View of Regeneration Part II

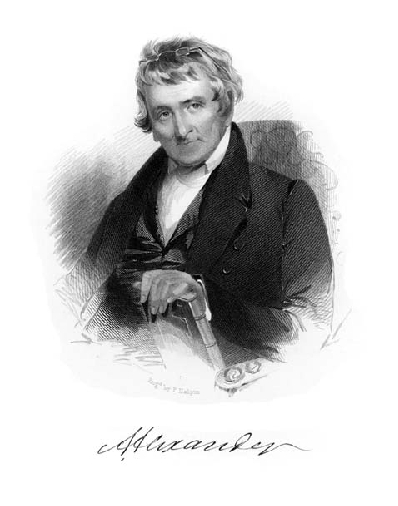

Archibald Alexander:

(April 17, 1772 – October 22, 1851) American Presbyterian theologian and

professor at the Princeton Theological Seminary.

Published in The Biblical Repertory and Princeton Review, volume 8 (1836).

The question is sometimes asked, whether is regeneration an instantaneous or

a gradual work? This is not a merely speculative question. If this is a gradual

work, the soul may for some time, yea, for years, be hanging between life and

death, and be in neither one state or nor the other, which is impossible.

Suppose a dead man to be brought to life by a divine power, as Lazarus was,

could there be any question of whether the communication of life was immediate?

Even if the vital principle was so weak as not to manifest itself at once, yet

its commencement must be instantaneous; because it may be truly asserted that

such a man is dead or alive; if the former, life has not commenced, and whenever

that state ceases, the man lives, for there is no intermediate state. So in

regard to the communication of spiritual life, the same thing may be asserted;

for whatever regeneration is, the transition from a state of nature to a state

of grace must occur at some point of time, the moment before the sinner was

unregenerate. This will be true even upon the principles of those who believe

that the exercises of the regenerate man are not specifically different from

those which are found in natural men under the common operations of the Spirit,

but that the difference is merely in degree. For according to this theory, there

will be some certain degree at which the man may be pronounced regenerate; at

any inferior degree he is unregenerate; then the moment in which he passes from

the next inferior degree to that in which regeneration consists is the moment of

regeneration. We suppose that they who are pleased with this notion of the

nature of regeneration would fix upon the time when pious feelings and desires

become predominant as the period when the man is regenerated; but this must

occur at some particular moment, and thus, regeneration is immediate and not

gradual. By gradual regeneration, however, they may mean a gradual preparation

for that state, by a continual increase of good desires and resolutions up to

the time when the man becomes a true Christian. Upon this hypothesis, the

correct way of speaking would be to say that the preparatory work was gradual,

but regeneration itself was instantaneous. As if the change were compared to the

entrance into some enclosure. The line of separation between the space within

and the space without is passed in a moment; yet in coming to it many steps may

have been required, and much time employed. But this theory of regeneration

which makes it to be nothing else but an increase of previously existing

principles is not consistent with reason, experience, or Scripture. Indeed,

there would be no propriety in the use of the word on this hypothesis: for such

a change would be nothing else but the growth of a principle already in

existence. To regenerate is to beget again, to give origin to a kind of life not

already existing in the person. Again, according to this theory, there may be an

almost inconceivably small difference between the regenerate and unregenerate.

Suppose the latter to have advanced to the point nearest to the line of

demarcation, of course the difference between him and the man who has actually

passed the line may be so small that it cannot be distinctly conceived: and yet

one of these is supposed to go to heaven, while the other is sent to hell. It is

true that grace in the feeblest saint prevails over sin and the world

habitually; but sometimes iniquities prevail against him for a season, as in the

case of David and Peter. Upon this theory the believer, in every such case, must

be fallen from grace; for if regeneration took place when good affections

predominated, when at any time they lose their predominance, the believer must

have fallen from his regenerate state, which opinion is held by some Arminians,

who maintain that both David and Peter had entirely lost the principle of grace

and had fallen into condemnation. But the true Scriptural doctrine is, that

there is a specific difference between the exercises of the regenerate and the

unregenerate. In the one there is true faith, sincere love to God, and genuine

repentance, whereas in the other, there are no such exercises, in any degree.

There may be resemblances and counterfeits, but in souls dead in trespasses and

sins, there exists no faith, no sincere love, nor any other exercise of the

spiritual life. The carnal mind is enmity against, and is not subject to the law

of God, neither can be. But when regeneration takes place, although the

exercises of piety may for a time be feeble, yet everlasting life is begun; such

a soul can never perish for it is united to Christ by an indissoluble union.

The commencement of this work is often involved in much obscurity, as in the

case of those who have been religiously educated, and have been early made the

subjects of the saving operations of the Holy Spirit. Such persons having never

run to the same excess of wickedness as many others, the change in their

external conduct is not very perceptible; and having been regenerated at a

period of life when their knowledge was small, and their judgment weak, they are

unable to determine satisfactorily the nature of their early impressions. In

consequence of this, and from observing a more remarkable change in others, they

are led to call in question the reality of their conversion. Indeed, there is

much danger lest unregenerate persons should, through the exceeding

deceitfulness of the heart, confound the tender impressions which are sometimes

experienced by youth religiously instructed, with the saving work of the Holy

Spirit. External regularity and decency of deportment, with a respect for

religion, and occasional fits of compunction, and strong desires of salvation,

have induced many to cherish a fallacious hope; and sometimes pious parents and

ministers from a solicitous desire to see the young taking their place in the

church, have been accessory to this delusion. And the danger of deception is

greatly increased, when artificial means of excitement are applied to a mind

tenderly awake to the importance of religion. Under such influences, many, after

a season of agitation, have experienced an animal exhilaration, or a calm which

naturally succeeds a storm, and have hastily taken up the fond persuasion that

they had experienced a change of heart, when all that has been felt is nothing

more than the workings of nature, or at most the convictions and desires which

arise from the common influences of the Spirit. When such persons are persuaded

to enter the communion of the church hastily, one of two events will ensue.

Either they will forsake their profession and fall back to the world; or they

will become formalists, and perhaps hypocrites, for life; secretly practicing

iniquity, and utterly neglecting the religion of the heart, and often of the

closet, while their public duties in the church are regularly, and it may be

zealously performed. For as such professors have it as an object to lead others

to think well of their religion, they will sometimes affect a zeal which is not

genuine, and will manifest a strictness bordering on rigor, in external rites

and observances. The savor of piety is however wanting, and the spirit of

Christian humility and meekness cannot be counterfeited: the very attempt

betrays the want of these tempers. And God in his righteous providence often

brings false professors into such circumstances, that their true character is

manifested to all men. They are permitted to fall into disgraceful sins in the

sight of men, or their secret crimes, in which they had long indulged, are made

public.

The conversion of some persons is so remarkable, either on account of the

greatness and suddenness of the change, or the clearness with which God reveals

Christ to their souls, that it is almost impossible for them to doubt the

genuineness of their conversion. Such a case was that of Paul. Such also was the

conversion of Col. Gardiner. The cases of John Newton and Richard Cecil are

somewhat different. They had both gone to great lengths in infidelity and

profligacy, so that the change was very great, yet it was not sudden but

gradual. Still they seem never to have doubted of the reality of their change.

The views and feelings of all regenerated souls are of the same kind, although

they may be exceedingly different in degree, and greatly modified by a variety

of circumstances. Probably every case of genuine religious experience has

something peculiar. The circumstances which commonly give complexion to these

exercises are constitutional temperament, early habits and associations, the

doctrinal knowledge possessed, the degree of terror or pungency of conviction

which preceded, and the nature of the truths which happen to be first

contemplated by the regenerated mind. It is a vain thing, therefore, to attempt

to give in exact detail and order, the exercises of the new creature. For one

man to make his own experience the standard by which to measure all other

Christians is as unreasonable as it would be to insist that all men should be of

the same stature, strength, and complexion. But in the midst of this diversity

there is a general likeness. The same truths operate on all, and the same

affections are excited in all. "If any man be in Christ, he is a new creature,

old things are passed away, behold all things are become new." Without

undertaking to describe the feelings of the renewed man in their actual

succession, we will speak of them in relation to the truths by which they are

produced. A regenerated soul has views of God's holy character and of his law,

different from any experienced before. The doctrinal or speculative notions may

have been correct or extensive, but to the intrinsic excellence of spiritual

objects, the unregenerate man is blind. "The natural man receiveth not the

things of the Spirit of God they are foolishness unto him, neither can he know

them because they are spiritually discerned." The view now enjoyed may be faint

and indistinct, but still it is of the right kind, and the emotions which

accompany it are new. A reverential fear of God is spread over the soul; a holy

awe takes possession of the mind. There is also a deeper impression of the

presence, power and majesty of God. His holiness is most distinctly contemplated

in the moral law, and we cannot behold the divine image in the glass, without a

deep conviction of our own sinfulness, and lively sorrow for the sins which we

have committed. These sins appear now to be exceeding base, and the soul is not

only penetrated with grief, but overwhelmed with shame, ceases not to condemn

itself for having consented thus to transgress a holy law, and is deeply humbled

in self-abasement before God. There is no longer any disposition to entertain

hard thoughts of God as being too severe, but he is fully justified in the

inmost convictions of the heart, and the penitent, instead of excusing or

palliating his own sins, takes upon himself the whole blame, and freely

acknowledges that God would be perfectly just in the infliction of the

tremendous penalty of his holy law. Indeed, the view of divine justice is

sometimes so clear, and that attribute appears so excellent, that the

enlightened soul cannot but approve his own condemnation. He fully acquiesces in

the righteousness of the divine administration, although he should be sent to

hell. "And if my soul were sent to hell, Thy righteous law approves it well."

Another emotion which is common to all penitents, is a pungent sense of

ingratitude to the best of beings and kindest of benefactors. There is no view

which so certainly breaks and melts the hard heart as a sense of God's goodness;

especially of his long suffering and patience which bore with us while we were

wickedly rebelling against him. If tears ever flow, this feeling will draw them

forth in copious floods. There is one view of sin however which produces an

effect without parallel. It is the representation of its abominable nature in

the cross of Christ, in the painful wounds inflicted on his body, in the

ignominy to which he was exposed, and above all, in the vials of wrath which

were poured out without mixture or mitigation on his holy soul. Here, as it were

in characters of blood, we see depicted the unspeakable turpitude and guilt of

sin. Here, at the foot of the cross, the love of sin receives a death-wound, and

the heart is divorced from all its long cherished idols. Now the solemn purpose

is formed to forsake sin, and to endeavor to live to God, in all holy obedience.

Christ appears glorious and lovely not only as a Savior but as a Lord; and there

is now no reluctance or hesitation about receiving him and trusting in him. For

a while the convinced and humbled sinner is kept back from closing with the

gracious terms of the gospel, by a legal spirit, by a sense of its own

unworthiness, and a fear that if it comes it will not be received. It cannot

conceive of that riches and freeness of grace which will welcome the chief of

sinners to the house of mercy. A lingering thought of some previous cleansing or

preparation; or at least of some deeper conviction, or more tender relentings,

prevents a speedy approach to Jesus. But O, when he manifests his love which

brought him from a throne to a cross, doubt and unbelief are driven away, and

like Thomas, the believing penitent exclaims, "My Lord and my God."

Where sin is truly repented of, there is always a willingness, and even a desire

to confess it. Therefore we read, "That with the heart man believeth unto

righteousness, and with the mouth confession is made unto salvation." Our

confession should be made chiefly unto God, for him have we offended. "Against

thee, thee only have I sinned and done this evil." And the sincere penitent

spends much time in humble prostration of soul before God, confessing with

brokenness of heart his multiplied and aggravated sins. He is ready to confess

faults before men, and especially before the church, so far as it is thought to

be for the glory of God and edification of the church. And if he has done

injustice to individuals, he wishes to confess the wrong, and is anxious to make

reparation, and even to do more. "Half my goods," said the converted publican,

"I give to the poor, and if I have wronged any man by false accusation, I

restore him fourfold." The prayer of another publican was, "God be merciful to

me a sinner."

It must not be passed over, though it would be understood by every experienced

reader, that such views as have been described cannot but enkindle a holy flame

of love to Christ, and to his cause and people. True faith cannot exist without

love — it works by love. The views of faith cause the love of God to be shed

abroad in the soul, and a sense of his love enkindles ours. "We love him because

he first loved us." God is love. This is the brightest and most amiable aspect

of his character; and when that divine excellence is manifested in unparalleled

love to us, it cannot but produce a powerful effect in winning the affections,

and drawing forth the heart in returns of love to him, "who has loved us and

given himself for us." Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down

his life for his friends: but God hath manifested his love by giving his only

begotten Son to die for us while we were enemies. The cross becomes the great

point of attraction to the believer, and the center of his warmest affections.

From this point radiate the brightest rays of the divine glory. From the cross

go forth the most potent influences to conquer the world, and to draw all men to

the Savior. The regenerate man lives by faith upon his crucified Redeemer.

Paul's experience is this, "I am crucified with Christ, nevertheless I live, yet

not I, but Christ liveth in me, and the life which I now live I live by the

faith of the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me." The new life

inspired in regeneration is a life of dependence — of entire dependence upon

Christ. The love of God in Christ is the animating principle of the new

creature. But graces rise not alone, they cluster together, and mutually support

and adorn each other. Faith works by love; faith and love united generate hope;

for the good which is loved and looked for, is not present but future. And when

hope rises to assurance it brings forth joy; and a sense of God's favor, and

confidence in his mercy and protection fills the soul with abiding peace; a

peace which the world cannot give, but which Christ often breathes into the

hearts of his disciples. "My peace I leave with you, my peace I give unto you,

not as the world giveth give I unto you. Let not your heart be troubled nor

afraid."

But although true religion consists essentially in right feeling, it does not

stop there, but goes forth into outward acts of obedience. Prayer and praise are

no longer a task, but a delight. Searching the Scriptures, and meditation on the

works and word of God, become the daily employments of the genuine convert; and

his progress in divine knowledge is often astonishingly rapid. He thirsts after

the knowledge of God, and his prayers for divine illumination are answered by

the gracious influences of the Holy Spirit, who by degrees leads him into the

knowledge of all necessary truth. The occasions of social and public worship are

pleasant and refreshing to the renewed man, and the sacred rest and holy

exercises of the Christian sabbath are in perfect correspondence with the taste

and temper of his mind. He is ready to exclaim, "I was glad when they said unto

me, let us go into the house of the Lord." "How amiable are thy tabernacles, O

Lord of hosts, my soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord."

"One day in thy courts is better than a thousand." A renewed heart is not only a

devotional but a benevolent heart. One of the strongest feelings experienced by

the person truly converted is a desire for the salvation of others. This

expansive desire may begin at home among his own kindred and friends, but it

will go on to enlarge the circle until it has no other limits but the ends of

the earth. Every man, however separated by distance or other circumstances, is

viewed as a neighbor and a brother, and the desire of happiness for all who are

not removed beyond the reach of mercy, becomes a cherished and predominate

feeling, and prompts to active exertions as well as fervent prayers in behalf of

those who are perishing in unbelief or for lack of knowledge. And the sincere

inquiry is made, "Lord what would thou have me to do?" To promote the glory of

God and the happiness of men are now the two great ends to which all plans and

actions are directed. With cheerful alacrity and steady purpose the regenerated

man begins a life of obedience and active usefulness. And as God has connected

him with others by various relations, out of which spring an obligation to

perform relative duties, he feels this obligation, and endeavors to fill up the

circle of prescribed actions with diligence and fidelity. Whatever may be his

condition in life, he will find enough to do. As a parent, a husband or wife, a

child or brother, a magistrate or private citizen, a teacher or pupil, a master

or servant, a friend or stranger, the law of God is so broad that it reaches his

case and embraces every relation of human life, whether natural or artificial.

The man who steadily performs these duties, and from day to day, like the sun,

goes through his prescribed course, is indeed a regenerated man, for the tree is

known by its fruits.

As this world is a place of trial and discipline, the child of God is not only

called to act with energy, but to suffer with patience. He who is taught of God

learns to be submissive to the divine will, and to bear with fortitude those

evils which are incident to pilgrims and strangers in this world. But while the

regenerated man experiences those exercises of piety which have been mentioned,

he is not free from feelings of contrary nature. The old man, or the deep-rooted

principle of sin, has received a deadly wound in regeneration, but the carnal

life lingers, and sometimes struggles with great force to recover the mastery of

the soul. Innumerable corruptions are bred in the heart, and often these hidden

evils are brought to view by the power of temptation, so that, for a season,

"iniquities prevail," and the unwatchful Christian is led captive by his

enemies; and if God did not reclaim him from his backsliding, he would be

utterly lost. The existence, at the same time, of two opposite principles in the

soul, of necessity produces a conflict. "The flesh lusteth against the spirit,

and the spirit against the flesh, so that we cannot do the things that we

would." This spiritual conflict is very painful, and the Christian soldier is

often astonished at himself, and is led to bewail his own imperfection and

inconsistency. He finds his enemies to be much more powerful and obstinate than

he expected, when he enlisted under the banner of the cross. He pleased himself

then with the prospect of an easy victory, and an almost unresisted progress.

Sin appeared to be dead; but the appearance was deceitful, it only lay concealed

in the depths of a deceitful heart. And when he finds the strength of his

corruptions, and the feebleness of his graces, he is often much discouraged, and

greatly fears that he shall one day fall by the hand of some of his numerous

enemies. The stability of the covenant of grace, and the faithfulness of God's

promises, are not at first fully understood; but gradually the sincere convert

learns to live by faith, knowing and feeling that all his strength and comfort

are treasured up in Christ. And after many painful contests, and some shameful

defeats, he has the pleasure of finding that his enemies give him less

disturbance than before, and learns to resist them more successfully, by means

of the word, prayer and faith.

A Practical View of

Regeneration Part III

|